Preface

ACEThe soil respiration monitoring technology was developed by ADC company in the UK based on the respiration chamber method. The ACE soil respiration monitor (ACE) consists of an automatic opening/closing breathing chamber and built-in CO2The rotating arm and control unit of the analyzer form a complete and compact field monitoring instrument, with two types of measuring instruments: closed measuring instruments and open measuring instruments, including closed transparent, closed non transparent, open transparent, open non transparent and other breathing chamber measurement methods. It can automatically and continuously monitor soil respiration, soil temperature, soil moisture and PAR at a fixed point. The whole machine is waterproof and dustproof, and the data is automatically stored in a storage card. The 12V 40Ah battery can continuously monitor for nearly one month in the field.

ACEIt is currently the only highly integrated instrument in the world that can be placed in the field for long-term soil respiration monitoring.

The researchers in the above figure measured using two types of breathing chambers: open transparent (left) and open non transparent (right)

Application field

uGlobal carbon balance research provides accurate data sources for carbon trading

uCombining climate change data to study the impact of greenhouse gas emissions on climate change

uCombining vorticity related data to provide a reasonable explanation for flux changes

uStudy on the influencing factors and regulatory mechanisms of soil respiration

uThe impact of different crops, cultivation types, or insecticides on soil respiration

uMicrobial Ecology

uResearch on the Restoration of Soil Pollution

uStudy on soil respiration status in landfill sites

working principle

ACETwo measurement modes are used: closed and open. The two modes use different working principles.

1Principle of closed measurement: Before starting the measurement, the breathing mask automatically closes, forming a closed breathing chamber. Inside the robotic arm adjacent to the breathing chamber, there is a high-precision CO2Infrared Gas Analyzer (IRGA). Analyze the gas in the breathing chamber every 10 seconds, and automatically calculate the soil surface flux (soil respiration value) by analyzing the data after the measurement is completed.

2Open measurement principle: The breathing mask automatically closes before starting the measurement. During the measurement process, the breathing chamber is connected to the ambient gas, and a pressure release device is installed at the top to maintain stable internal and external air pressure. Measure the CO in and out of the pumped gas after reaching steady state at a certain flow rate2Calculate the flux value automatically based on the concentration difference Δ c.

Features

lHighly integrated, fully automated, and integrated soil respiration monitoring system with automatic opening/closing of breathing chambers, CO2The analyzer, data collector, and operating system are integrated together, making it easy to carry and move, without the need for additional external devices such as computers, and without complex and time-consuming installation processes such as pipeline connections

lBuilt in microcomputer five key operating system, large 240 × 64 dot matrix LCD screen for setting operations, data browsing, and diagnosis

lThere are closed and open options available for selection. In arid areas with weak soil respiration, it is recommended to choose closed measurement

lThe breathing chamber area reaches 415cm2There are transparent and non transparent breathing chambers to choose from. The former is suitable for measuring carbon flux in low growing herbaceous or seedling communities, or for measuring soil carbon flux in soils with a large number of photosynthetic algae (such as blue-green algae), mosses, and lichens (which have both photosynthesis and respiration)

lHigh precision, high sensitivity CO2Analyzer with a resolution of 1ppm

lCan connect 6 soil temperature sensors and 4 soil moisture sensors to monitor soil moisture and temperature in different profiles

lThe power supply method can be selected from three options: solar energy, battery, and 220V AC power

lMultiple ACEs can be purchased for multi-point monitoring, and several transparent and non transparent breathing chambers can be selected for monitoring and analyzing soil and aboveground photosynthetic organisms (such as biofilms, mosses, low vegetation, etc.), including total photosynthesis, net photosynthesis, total respiration, net respiration and their interrelationships, as well as diurnal dynamic patterns

technical indicators

lInfrared gas analyzer: Built into the soil breathing chamber, with a short gas path and fast response time

lCO2Measurement range: Standard range 0-896ppm (customizable large range and range) Resolution: 1ppm

lPAR:0-3000μmol m-2s-1silicon photocell

lSoil temperature thermistor probe: measurement range: -20-50 ℃, can connect up to 6 soil temperature probes

lSoil moisture probe SM300: measuring range 0-100vol%; Accuracy of 3% (after calibration for soil); Measurement range of soil: 55mm x 70mm; Can connect up to 4 soil moisture probes

lSoil moisture probe Theta: measurement range 0-1.0 m3.m-3Accuracy ± 1% (after special calibration) probe size; Probe 60mm long, probe total length 207mm; can connect up to 4 soil moisture probes

lRespiratory chamber flow control: 200-5000ml/min (137-3425 µ mol sec)-1)Accuracy: ± 3% of flow rate

lBreathing chamber types: open transparent, open non transparent, closed transparent, and closed non transparent. There are four types of breathing chambers to choose from

lInstrument operation: independent host, no need for PC/PDA

lData recording: 2G mobile storage card (SD), capable of storing over 8 million sets of data

lPower supply: external battery, solar panel or wind power supply, 12v, 40Ah battery can last for up to 28 days, only network type has internal battery 1.0Ah

lData download: Read SD card or connect via USB

lElectronic connection: sturdy and waterproof 3-pin socket (head)

lProgram: User friendly interface, controlled by 5 keys

lGas connection: 3mm gas path connector

lDisplay: 240 × 64 dot matrix LCD screen

lSize: 82 × 33 × 13cm

lSealed chamber volume: 2.6 L

lOpen room volume: 1.0 L

lSoil breathing mask diameter: 23 cm

lWeight: 9.0 kg

The left side of the picture shows the pre embedded steel ring, and the right side shows the physical image of ACE connecting soil moisture and soil degree sensors

Selection of breathing chambers

The difference between closed and open

Closed measurement involves the complete closure of the breathing chamber during measurement. Simple measurement and fast speed(5-10mins)The application is the most common. But the accuracy is relatively low |

The difference between transparent and non transparent

Non transparent breathing chamber, only measuring respiration (including soil respiration and plant aboveground respiration) |

Operation screen and results

Application Cases

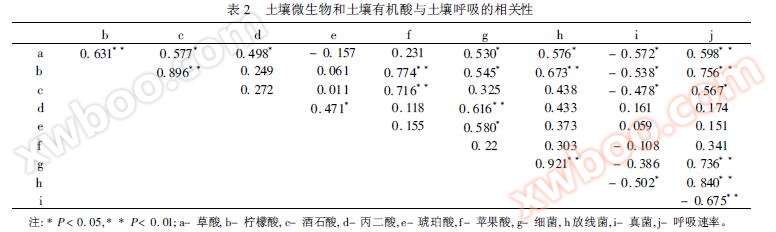

Qu Ran et al. (2010) used ACE to study the effects of soil microorganisms and organic acids on soil respiration in Qinling Mountains. Research has shown that soil respiration rate is significantly positively correlated with soil bacteria, actinomycetes, oxalic acid, and citric acid.

Place of Origin

the United Kingdom

Optional technical solutions

1)Multiple ACEs can be optionally configured for multi-point monitoring, forming a network monitoring solution with ACE MASTER host

2)Optional soil oxygen measurement module

3)Optional hyperspectral imaging for evaluating soil microbial respiration

4)Optional infrared thermal imaging for studying the effects of soil moisture and temperature changes on respiration

5)Optional ECODRONE ® Unmanned aerial vehicle platform equipped with hyperspectral and infrared thermal imaging sensors for spatiotemporal pattern investigation and research

Partial references

1.K. Krištof, T. Šima*, L. Nozdrovický and P. Findura (2014). The effect of soil tillage intensity on carbon dioxide emissions released from soil into the atmosphere” Agronomy Research 12(1), 115–120.

2.Xinyu Jiang, Lixiang Cao, Renduo Zhang (2014). Changes of labile and recalcitrant carbon pools under nitrogen addition in a city lawn soil. Journal of Soils and Sediments, March 2014, Volume 14, Issue 3, pp 515-524.

3.Cannone, N., Augusti, A., Malfasi, F., Pallozzi, E., Calfapietra, C., Brugnoli, E. (2016). The interaction of biotic and abiotic factors at multiple spatial scales affects the variability of CO2fluxes in polar environments” Polar Biology September 2016, Volume 39, Issue 9, pp 1581–1596.

4.Liu, Yi, et al. (2016). Soil CO2Emissions and Drivers in Rice–Wheat Rotation Fields Subjected to Different Long‐Term Fertilization Practices. ” CLEAN–Soil, Air, Water (2016). DOI: 10.1002/clen.201400478 ( http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/clen.201400478/abstract ).

5.Xubo Zhang, Minggang Xu, Jian Liu, Nan Sun, Boren Wang, Lianhai Wu (2016). Greenhouse gas emissions and stocks of soil carbon and nitrogen from a 20-year fertilised wheat maize intercropping system: A model approach” Journal of Environmental Management, Volume 167, Pages 105-114, ISSN 0301-4797, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.11.014. ( http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301479715303686 ).

6.Altikat S., H. Kucukerdem K., Altikat A. (2018). Effects of wheel traffic and farmyard manure applications on soil CO2emission and soil oxygen content” Thesis submitted from the “Iğdandr University Agriculture Faculty Department of the Biosystem Engineering”.

7.Cannone, N. Ponti, S., Christiansen, H.H., Christensen, T.R., Pirk, N., Guglielmin, M. (2018).“Effects of active layer seasonal dynamics and plant phenology on CO2land atmosphere fluxes at polygonal tundra in the High Arctic, Svalbard” CATENA, Vol 174 (March 2019) 142-153. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0341816218305009 .

8.Uri, V., Kukumägi, M. Aosaar, J.,Varik, M., Becker, H., Auna, K., Krasnova, A.,Morozova, G.,Ostonen, I., Mander, U., Lõhmus, K.,Rosenvald,K., Kriiska, K., Soosaarb, K., (2018). The carbon balance of a six-year-old Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) Forest Ecology Management 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2018.11.012